A NEW SEASON

A New Season

by author Terry Fallis

Read by John Butler

From beloved and bestselling author Terry Fallis comes a novel unlike any of his others. A thoughtful exploration of aging, loss, family, friendship, and love, all with his trademark humour and heart.

Jack McMaster is learning to live with loss. He passes his days knowing he has the support of his family and his friends, but Jack can’t shake the feeling that his life has gone gray, and that time is slipping by so quickly.

Inspired by his lifelong fascination with 1920s Paris, Jack finally visits the City of Light, following the footsteps of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and wandering the Left Bank. Slowly, the colour seeps back into his life, aided by a chance encounter in a café that leads Jack into the art world, and a Paris mystery nearly a century old.

Full of sincerity and warmth, A New Season shows us all that sometimes, making a change can save your life.

John Butler reads A New Season, representing the community of Grey Highlands.

John, a retired community health and social service planning consultant, was the founder and President of The Agora Group of human service consultants. He lives on a rural property near Port Law in Grey Highlands with his wife June and a gaggle of pets.

A student of local history, he is the author of House of Refuge, a book about the first few years, in the early twentieth century, of Grey County’s home for elderly and indigent people (his co-author, Frederick Gee — an inmate of the House — passed away 118 years ago).

He has a passion for works of fiction and nonfiction about the creation and growth of communities, and how they nurture us and strangle us at the same time. An avid climate activist, John is a member of the Grey Highlands Climate Action Group and writes an occasional newsletter, The Village Green, on climate and environmental issues.

Introduction

I’m a pushover for authors who make me a co-conspirator from the very beginning of their book — who turn me into a confidante as the story unfolds. This is what Terry Fallis does in his novel A New Season (McClelland & Stewart, 2023). What he writes reads more like conversation than narration. His lead character, Jack McMaster, actually seems to care what the reader thinks of him.

Jack , a 63 year old Toronto freelance writer dealing with the death of his wife, is as Canadian as he can be — talented but self-deprecatory, willing to confess his shortcomings without being paralyzed by them, applying humour like a salve to his wounds. I like him.

Jack is anchored throughout the greyness of his bereavement by his love for his grown son Will, by steadfast friends from the ball hockey team he co-captains, and by something beyond his here and now — a fascination with the Lost Generation of writers and artists who flourished in Paris in the 1920s. At the urging of his dead wife, his five-month visit to Paris becomes a voyage of exploration into the era that fascinates him, but a journey as well into an intimacy he felt would never be his again.

And he takes us with him.

Plot Summary

Jack McMaster is living a monochromatic life two years or so after his wife Annie died of Covid. His son Will, a talented chef and sound engineer, transcends his own grief at the loss of a mother to care deeply about his father’s fate. Will feels the time is right to play for his father a video message Annie recorded for Jack just before she died — “Go to Paris like we planned. Go for me. Find someone. Be good to someone. Be good for someone. “

Jack leaves the comfort zone of his son and his ball hockey friends to live for five months in a flat in the heart of the Left Bank in Paris. There he walks in the footsteps of Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Picasso and Canadian writers John Glassco and Morley Callaghan. He haunts the cafés they haunted, and in one of them he meets café worker and painter Calla — a 56 year old English woman who has lived for years in the Parisian flat her grandmother, Constance Stanley, bequeathed her. Jack becomes fascinated by Calla when he finds out that her grandmother had been part of the Lost Generation’s coterie of artists — and finds out that Calla’s name is actually Callaghan Hughes, named after Canadian writer Morley Callaghan, whose memoir That Summer in Paris detailed Parisian artistic life in the 1920s. Jack also appreciates her as a kindred spirit going where her curiosity leads her, and as a warm breeze of honesty and unconventionality.

They become intimate friends — a deep romance of sorts — but not lovers, in part because Jack isn’t ready to move from Annie’s memory, and in part because Callaghan doesn’t want to intrude on that memory. Yet each of them blossoms in the company of the other. A song written decades earlier by Jack for his young wife Annie is discovered and recorded by Blue Rodeo’s Jim Cuddy (a real-life friend of author Fallis) and the song climbs Canada’s Christmas song charts. A major Paris exhibition of Callaghan’s painting sells out. Together they realize that a multi-volume set of grandmother Constance Stanley’s diaries, treasured by Callaghan for years, provides insights into the Parisian lives of the Lost Generation and should be published, along with her photos and a secret diary they discover that details Constance’s intimate relationship with iconoclastic 1920s singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Jack edits the diaries and Oxford University Press publishes them to great acclaim.

But looming unspoken between them is Jack’s intention to return to Canada. He hopes to maintain a long distance romance with Callaghan, but her memories of a past broken relationship impel her to end their relationship, tearfully for both of them, as he departs.

Do they rekindle their romance, in Toronto or in Paris, or not at all? Read A New Season to find out.

Character Analysis

Not surprisingly Jack McMaster, as narrator, is the central character. He lives in anticipation of disappointments small and large, yet he’s grateful when surprises, small and large, turn out to be good, not bad. As he says as he de-planes in Paris, “It was an uneventful flight. I mean, no oxygen masks dropped from there ceiling panels above our heads. No one threw up on the passenger in front of them. And no one complained that the pretzel packages were too large.”

Jack is gregarious but not overbearing — prone to affectionate mock insults when he talks to his ball hockey mates, prone to a gentler humour in his witty and literate conversations with soulmate Callaghan. He tells us of himself and implicitly asks for our indulgence — “I may not have mentioned it yet — in fact, I know I haven’t. I am sixty-two. There, I said it. I still don’t believe it, but at least I said it. Yes, I’m as shocked as you are.” He is a man who disarmingly shows us how he must learn to yearn for the future, not only the past. He’s much like the rest of us.

Callaghan Hughes shares one crucial characteristic with Jack — they both wear feelings close to the surface, They are both ready to laugh and provoke laughter, yet their tear ducts work overtime at times when faced with the sad or the inexpressibly beautiful. Like Jack, Callaghan has her anchors — the memory of her beloved grandmother Constance, her love of life in Paris, her art, her curiosity. She puts Jack’s visiting family and friends at ease because she is at ease in the presence of others — she confesses to Jack late in the novel that she keeps her job serving customers in a café not because she needs the money, but because she needs contact with people to countervail the isolation the comes from her time spent painting. Through Jack’s eyes, she’s not like the rest of us.

This third major character is Jack’s son Will, adept at cuisine, music, repartee, and serving as his father’s life raft in the face of their shared grieving. With the mix of affection and mock condescension common in our grown children, he looks after his dad.

A fourth and congregate character is his ball hockey team. We get glimpses of individual teammates but the team trumps the individuals. Author Fallis says that he used the ball hockey league to explore male friendship in A New Season. As Jack says about his team, “It’s a community of good friends who really care about one another and look out for one another.” He even writes a song about his team, and gives us its lyrics in the book.

Another major character of sorts is Paris itself, a place Jack sees through different lenses. One is the lens of art and history – the lens that drew him to the city in the first place. Another is the lens of a newcomer — Jack is as wide-eyed and naive as any other tourist when he arrives, and he shares with us his touristic delights, embarrassments and irritations. “Perhaps I was destined to become blasé about it all. I hoped not,” says Jack. And Paris is also home for a time, a place where he is happy and adept. Much of the novel’s tension comes from his unfolding love of Paris (particularly the Left Bank and its people), and his longstanding love of Toronto (particularly Riverdale and its people.)

The book has its share of ghosts of sorts — spectral motivators if you will, whose lives have shaped the living. Jack’s deceased wife Annie is a constant presence. What she told him to do from her deathbed, and how she might have reacted to the actions he contemplates after her death, are part of his operating manual. Callaghan’s grandmother Constance, chronicler and denizen of the Lost Generation, set the trajectory of Callaghan’s life. And there are the giants from Paris in the 20s who make a brief appearance – Ernest Hemingway (good writer, lousy human being), his first wife Hadley (much more likeable), imperial Gertrude Stein, the sensual and artistically daring and beautiful Josephine Baker — all of them are reasons why Jack is there a century later.

Theme Analysis

Terry Fallis is adept at layering meanings and themes in his works. For me, this novel has much to say about what happens when chained yearnings become unchained. Whether it’s Jack’s yearnings for a multicoloured life again (chained by his grief and the sense of responsibility he feels he owes to Annie’s spectre) or Callaghan’s yearning for the man who shares her life’s interests (but chained by the calendar that draws Jack away), yearning isn’t a straight road to fruition. And both Jack and Callaghan play out their yearnings in a part of Paris that saw the yearnings of young artists play out in the 1920s. I think Jack and Callaghan would say yearning is in the very air of the City of Lights, as much for middle-aged dreamers as for the young.

Fallis has made it clear that this book is about also brotherness (and by extension, sisterness) — the doing of things with others, a doing that builds respect and support. Ball hockey is his chosen example because Fallis is himself a longstanding member of a Toronto ball hockey team. But the example is less important than the lesson — that in a world sometimes dismal, sometimes unkind and sometimes cold, the warm shoulder of a teammate — a friend — is a pretty good place to be.

Relevance for today

Since yearning and loving are lifelong twins, this novel has much to say to those of us who are more grey than green — those of us with scars and successes marking our passage through time, those of us who have learned – or want to learn — that laughter and friendship are condiments leading us to the taste of love.

For younger readers caught up in the immediacy of fresh strange love, the book has value too. Know that you will become Callaghan and Jack. And that’s not a bad fate at all.

We live in uncertain — some would say frightening — times. Many of us have moved from here to there and back again, chasing what careers or other pragmatics tell us we must find. Yet Callaghan and Jack tell us to find a place when there is love to be given and taken. There, ultimately, we should be.

Summary

With nine books under his belt, Terry Fallis is known for his novels that we find on the humour shelf in bookstores, and he has twice won the Leacock Medal for Humour — yet I see A New Season as a love story. If you’re looking for a book that provokes yuks and guffaws, this ain’t it.

Yet there’s humour in the book — the kind that comes from casting a sympathetic eye on the foibles of our inconsistent lives. Early in the book, Jack gives a reason he feels his age — asserting it is the only reason. A few score pages later another reason he asserts is his last . Twenty or so pages later, again his last reason, so he says. Then yet another. He tops out at twelve reasons by the end of the book. And we offer up a smile as Jack, proud of his conversational French, repeatedly orders things in Paris cafés in French, only to get responses in English (those of us who’ve tried out our French in Quebec bistros know how he feels.) Fallis makes sure, though, that the humour in his book is never unkind to others – his characters mock only themselves.

This is a tale of two people who find each other through the elucidating light of coincidence (or fate as Callaghan would put it). And while Jack McMaster has beloved anchors (his son and his ball hockey team and the memory of his wife), he has sails and a hull too, made seaworthy by his dead wife’s wish and hope for him. He persuades us to join him, not as crew under his command, but as fellow yearners and learners sailing to somewhere new.

The voyage is worth it.

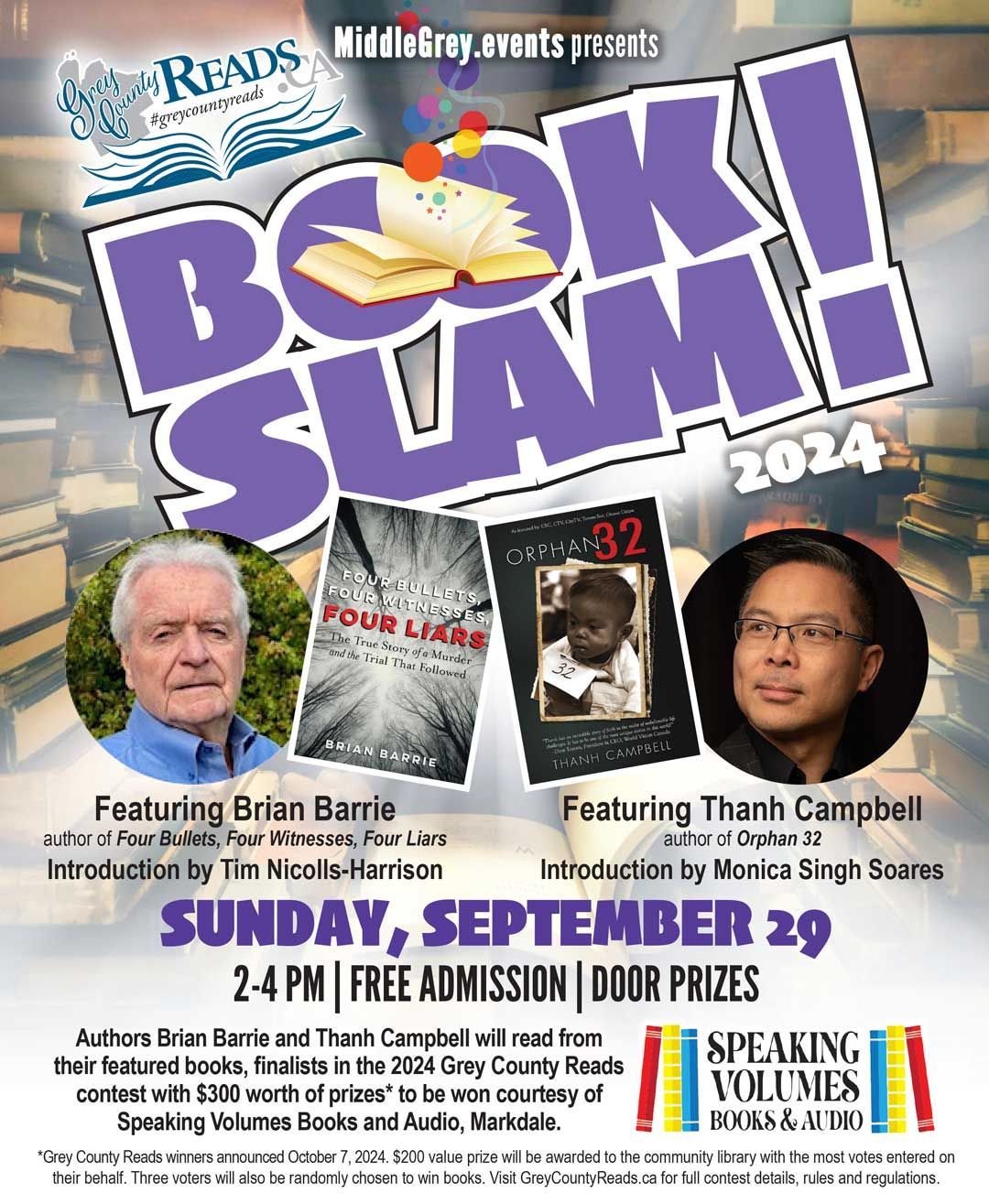

Grey County Reads is supported through advertising by these local businesses and organizations:

Alex Ruff, MP Bruce-Grey-Owen Sound

The Colour Jar

ColourPix Website Design and Personalization Services

Grey Roots Museum & Archives

Hanover Chamber of Commerce

Leaking Ambience Studio

Leela's Villa Inn

Linda Sachs Books

The Market Shoppe

Meaford Chamber of Commerce

Mullin Bookkeeping

Speaking Volumes Books & Audio

South Grey Chamber of Commerce

Grey County Reads is a production of ColourPix.

Contact Us

Visit our contact page to get in touch.

Vote for your favourite book and get notified about Grey County Reads